Anna Politkovskaya, and The Dictators

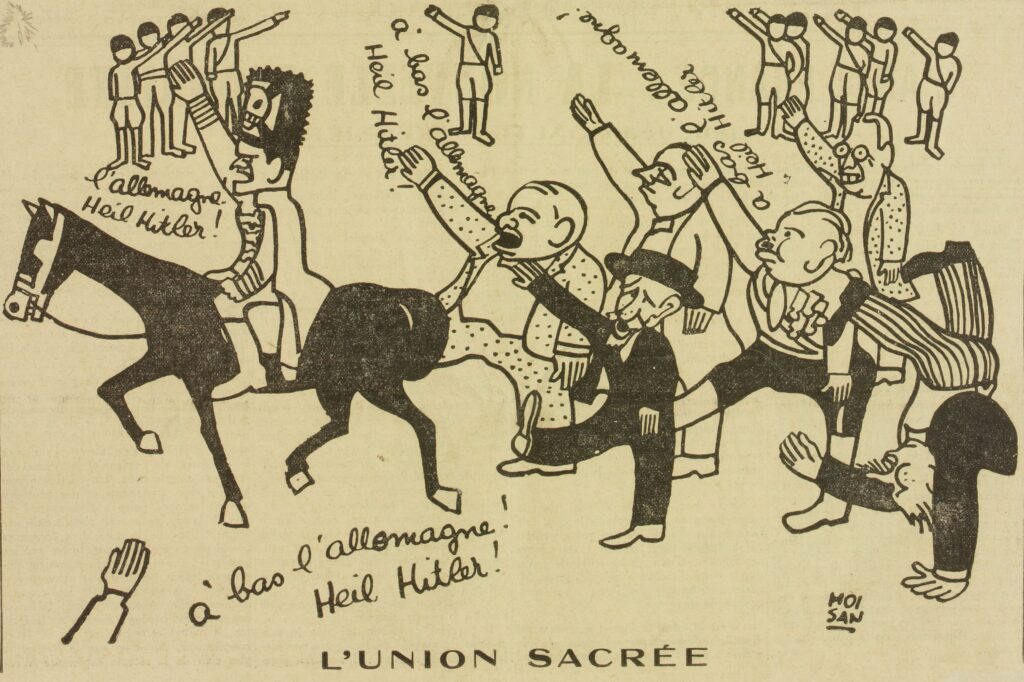

“Shall we be forced to admit to our children and grandchildren that we aided this fascism, and did nothing to prevent it happening?”

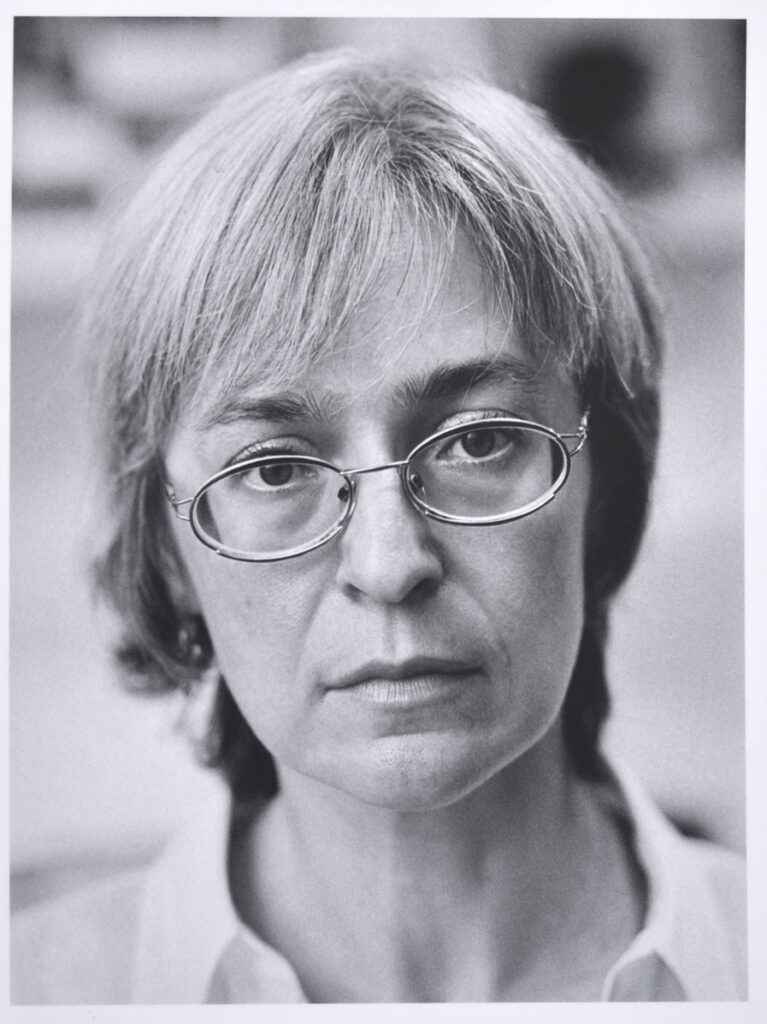

Anna Politkovskaya is what every journalist is supposed to be, claims to be – and shines out in our dark moment with her insistence on truth as the only thing worth living and dying for. Her influence in her country Russia, and far beyond, continues to radiate today, two decades after her murder – all the way to her birthplace, the USA, where she was born to Soviet diplomats. Even warmonger and torturer George W. Bush issued a statement in homage to Politkovskaya after her 2006 assassination by Putin’s regime on Putin’s birthday. Something unthinkable for 47 and today’s GOP.

It is no surprise that the first biopic of her life – Words of War – was made in England and not by Hollywood, which has even less interest in press freedoms ever since the self-censorship started with the Hays code. And it is no surprise that, if you’ve read all of her work, the film can only touch on some parts of her life and leave others entirely out, but not to its detriment. Instead, the film lets her work, and her life of mind-boggling bravery, stand for itself, while balancing the story with the deep family life she lived and the intense struggle such families endure for such insistent truth-seekers in a dictatorship. And the film gives glimpses of the silly Anna – the person who loved life and wanted to share and save that love for others. (One example of this fun-Anna not in the film appears after Anna’s death, her friend Elena Morozova recalled Anna’s “favorite message” to leave on Elena’s answering machine: “Hello, this is Anna Politkovskaya. I live just across the road. Call me.”)

Actress Maxine Peake plays Anna with the journalist’s compassion and fearlessness; as the truth-teller who is constantly flabbergasted that there are others in the world who don’t care about truth in the least, like the character in The Silver Fleet working to undermine the Nazi occupation in his country who scoffs, “What fools they are – they think life is everything.”

And since Anna wrote a great amount in her truncated time here, most of this article will be her words, and how we can use their wisdom and bravery and integrity to fight for the world we deserve.

Perhaps the greatest difference between Russia and the USA, as seen in Politkovskaya’s words, is that the USA is the world’s oldest democracy, and Russia has had very little of that – although she describes the sad state of magas and their dependence on a man who hates them. And it is perhaps not an insane hope to believe that the good people of the USA, and angels of our better histories, will not tolerate authoritarianism:

“Our [Russian] people … They want very much to live better lives, but do not want to have to fight for that. They expect everything to come down to them from above, and if what comes from above is repression, they resign themselves to it.”

“Our democracy continues its decline. Nothing in Russia depends on the people; everything depends on Putin. There is an ever greater centralization of power and loss of initiative by officialdom. Putin is resuscitating our ancient stereotype: ‘Let us wait until our lord the barin comes back. He will tell us how everything should be.’ It has to be admitted that that is how the Russian people like it, which means that soon Putin will throw away the mask of a defender of human rights. He won’t need it anymore.”

“Our society is sick. Most people are suffering from the disease of paternalism, which is why Putin gets away with everything, why he is possible in Russia.”

An exchange in Words between Anna and Nestor (Oliver Maltman), a journalistic colleague, is descriptive of magas who claim patriotism while hating everything good about the USA:

Nestor: “Putin made it ok to love our country again.”

Anna: “Some of us never stopped.”

Politkovskaya suffered under and described a Russia very much like what 47 wants to create in the USA:

“The only thing that matters in Russia today is loyalty to Putin. Personal devotion gains an indulgence, an amnesty in advance, for all life’s successes and failures. Competence and professionalism count for nothing with the Kremlin. The system that has evolved under Putin profoundly corrupts officials, both civilian and military.”

In spite of her culture’s insistence that resistance is futile, she knew protests work:

“The whole system of thieving judges, rigged elections, presidents who have only contempt for the needs of their people, can operate only if nobody protests. That is the Kremlin’s secret weapon and the most striking feature of life in Russia today. That is the secret of spin doctor Surkov’s genius: apathy, rooted in an almost universal certainty among the populace that the state authorities will fix everything, including elections, to their own advantage. It is a vicious cycle.”

And Putin knows protests work, too – that’s why he and his boy 47 seek to repress them so harshly:

“One of the reasons for Russia’s social malaise is this diabolical cynicism on the part of the authorities, who peddle a completely fake reality. Russia’s citizens do not rise up against this cynicism. They withdraw into their own shells, becoming defenseless, wordless, and inhibited. Putin knows this and employs brazen cynicism as the antirevolutionary technique that works best in Russia.”

But the only thing that has ever changed the world is You:

“The habit of considering yourself a ‘small person’ is like the red button in the president’s nuclear suitcase – he has only to press it and the country is in his hands. I am quite sure that Putin and his entourage fight corruption solely for PR purposes. In reality, corruption is very much to their advantage; it plays an important role in conditioning people to keep quiet. While the courts are pulled this way and that by the criminals and the politicians, he has nothing to fear.”

Because the powerful are very fearful snowflakes who know their own incompetence and emptiness:

“The authorities’ apparent contempt for their own citizens stems from their fear of us. They cannot face our grief, they cannot admit their own shortcomings or acknowledge their responsibility for the many victims…”

They also need to lie about the huge influence freedom-seekers have on the culture, as seen in Putin’s wishful words after his assassination of Anna: “…the extent of her influence on political life in the country, in Russia, was extremely insignificant.”

Politkovskaya wrote about her own culture, but could have been describing our magas’ cruel indifference to others while thumping a Bible:

“How we react to the tragedy of one small person accurately reflects our attitude towards a whole nationality; and increasing the numbers doesn’t change much.”

Her description of Russia in 2006 smashes any USAer in 2025 with breathtaking relevance:

“There is something fundamentally wrong in Russia. Life has been turned upside-down and the law has no substance. The entire range of public services is put to work on behalf of the criminal: the lawyers, Prosecutors, courts – and even, sad to relate, public opinion.”

And for celebrities? She interviews one Russian actress who explains their customary fealty to power:

“If I didn’t mention Putin, our local FSB [KGB] man would be round to see me in the shop tomorrow to complain I wasn’t saying what everybody says. That’s the kind of life we busineses people lead now.”

Her description of Russia’s cronyism describes Eric Adams’ sycophantic and pathetic relationship to 47:

“It is all just the way it is in Chechnya. The regime takes people under its wing who have, preferably, several criminal cases pending against them. These are quashed in return for a guarantee that ‘While you are with us, nobody can raise a finger against you. You beat up those we point out.’ (In Chechnya, ‘You kill on our say-so.’)”

In describing Putin’s imperialism, she described 47’s pathetic longing to take over Canada, Panama, Greenland, etc. – what Gore Vidal called “the enemy of the month club”:

“The genocide of one people, however, soon leads to the genocide of another, a truism borne out through the centuries by successive generations of invaders and those invaded. For the totalitarian empire being constructed in front of our eyes, punitive expeditions give life meaning. Today one group is sent to the guillotine, tomorrow a different one. The day after tomorrow, it will be the turn of little Liana, and later still, we need have no doubt, it will be our turn.”

In describing what Putin has done to the justice system of Russia, she describes 47’s pardons of January 6 traitors:

“That is the reality of selective justice. Criminals are freed while political prisoners get put in chains, thrown in prison, kept in cages. The authorities rely on criminal elements to prop up the system of state power.”

And she describes that devastating sign of dictatorships: The Disappeared:

“…in Russia the abduction of people by state employees, and extra-judicial penalties meted out by them (our Abu Ghraib), continue because the state, in the guise of the Prosecutor’s Office, covers up for those who have enough stars on their epaulettes. The state does not search for the disappeared, and families are thrown back entirely on their own resources.”

She describes the despair of those Putin-supporters who have seen their own lives destroyed by their hero:

“Some of the mothers of children who died at Beslan have locked themselves in the court building in Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia, where Nurpasha Kulaev is being tried. Officially, he is the only surviving terrorist of all those who seized the school.

After the tragedy, the mothers said they trusted only Putin and had every confidence he would ensure an objective inquiry. Putin promised that he would. A year has passed. The inquiry, however, exonerated all the bureaucrats and security agents who planned and carried out the assault that led to the deaths of so many children and adults. The women are now demanding that they themselves be arrested. They consider themselves responsible for the deaths of their own children, because they voted for Putin. Their sit-in is an act of desperation.

‘We, the mothers of Beslan,’ Marina Park says, ‘are guilty of having given life to children doomed to live in a country that decided it did not need them. We are guilty of having voted for a president who decided children were expendable. We are guilty of having kept silent for ten years about the war being waged in Chechnya, which has brought forth rebels like Kulaev.'”

And she describes the despair of those who cannot adjust themselves to a purposefully-cruel society, like her son’s friend Ilya who somehow survived the Nord-Ost tragedy, who now “sees a reason to fight everywhere” and asks Anna:

“What’s wrong with me?”

“You just need to be treated.”

“I can’t stand seeing injustice. How can the hospital help with that?”

Having been assassinated by/for Putin’s regime, after years of abuse from same, Politkovskaya knew all the risks of being a journalist, and of being without them:

“Every successive attack on a journalist in Russia – and by tradition nobody ever gets caught – relentlessly reduces the number of journalists working because they want to fight for justice. The risks are very great and not everyone is up to the unremitting tension which accompanies this kind of work. As the numbers of one kind of journalist fall, so there is an increase in the number of those who prefer undemanding journalism, reporting which doesn’t involve prying where you are not welcome.

Undemanding media cater for an undemanding public, ready to agree with everything it is told. The more there is of the former, the more monolithic the latter becomes, and the less opportunity society has of seeing what is wrong with the circumstances in which it lives.”

Her description of the plight of truth-telling journalists is entirely like ABC’s recent dismissal of Terry Moran for his rather uncontroversial statement about hatemonger Stephen Miller:

“The editor in chief of Izvestiya, Raf Shakirov, has been fired. He was a careerist: not a revolutionary, not a dissident, not a chamption of human rights. He was fired for failing on just one occasion to intuit the new state ideology, something that is not supposed to need spelling out. Izvestiya published a brutally honest photographic report from Beslan about the assault on the school. The authorities complained that it was too shocking.

Izvestiya is not a state-owned newspaper – it belongs to the oligarch Potanin – but thunderclouds were gathering over Potanin just like those that had gathered over Khodorkovsky. By firing Shakirov, Potanin must hope he is back in with Putin and the Kremlin.”

She explains in her book about Chechnya exactly what USA’s media is up to:

“…the time of Putin is the time of silence about what’s most important in this country.”

Her definition of a journalist will appear revolting to mainstream U.S. media that has collaborated in the rise of fascism under 47:

“A journalist is above all someone who does not lie and will check facts many times before risking an error.”

She wrote about the poison that starts at the top, and spreads to the population at large, particularly to those with little love in their hearts and with close connections to police – so like the maga-murder of six-year-old Wadea al-Fayoume:

“In St. Petersburg, skinheads have stabbed to death nine-year-old Khursheda Sultanova in the courtyard of the apartments where her family lived. Her father, thirty-five-year-old Yusuf Sultanov, a Tadjik, has been working in St. Petersburg for many years. That evening he was bringing the children back from the Yusuprov Park ice slope when some aggressive youths starting following them. In a dark connecting courtyard leading to their home the youths attacked them. Khursheda suffered eleven stab wounds and died immediately. Yusuf’s eleven-year-old nephew, Alabir, escaped in the darkness by hiding under a parked car. Alabir says the skinheads kept stabbing Khursheda until they were certain she was dead. They were shouting, ‘Russia for the Russians!’

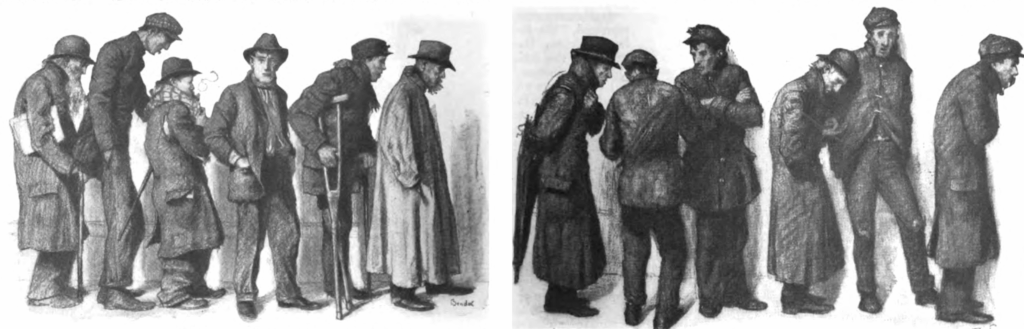

The Sultanovs are not illegal immigrants. They are officially registered as citizens of St.Petersburg, but fascists are not interested in ID cards. When Russia’s leaders insults in sound bites about cracking down on immigrants and guest laborers, they incur responsibility for tragedies such as this. Fifteen people were detained shortly afterward, but released. Many turned out to be the offspring of people employed by the law enforcement agencies of St. Petersburg. Today, 20,000 St. Petersburg youths belong to unofficial fascist or racist organizations. The St. Petersburg skinheads are among the most active in the country and are constantly attacking Azerbaijanis, Chinese, and Africans. Nobody is ever punished, because the law enforcement agencies are themselves infected with racism. You have only to switch off your audio recorder for the military to start telling you they understand the skinheads, and as for those [B]lacks . . . etc., etc. Fascism is in fashion.”

And she wrote about the docility of giving up:

“A depraved society wants comfort for itself and peace and quiet, and doesn’t mind if the cost is other people’s lives. People … would rather believe the State’s brainwashing machine than see the reality.”

“These are people who love and trust Putin without reservation, irrationally, uncritically, fanatically. They believe in Putin. End of story.”

“It may seem to you, my readers, that your continuing support for the war gives you the right to pass sentence on another human being. Yet when you imagine that you can obtain if not happiness then at least peace of mind at the cost of another’s life you are making a tragic mistake. I can only say that no one’s peace of mind is worth the death of another human being. Retribution is sure to come. Moreover, it does not come to us together, which would be easier to bear, but to each individually. Then we have to face a single choice: either we end this war or it will be the end of us.”

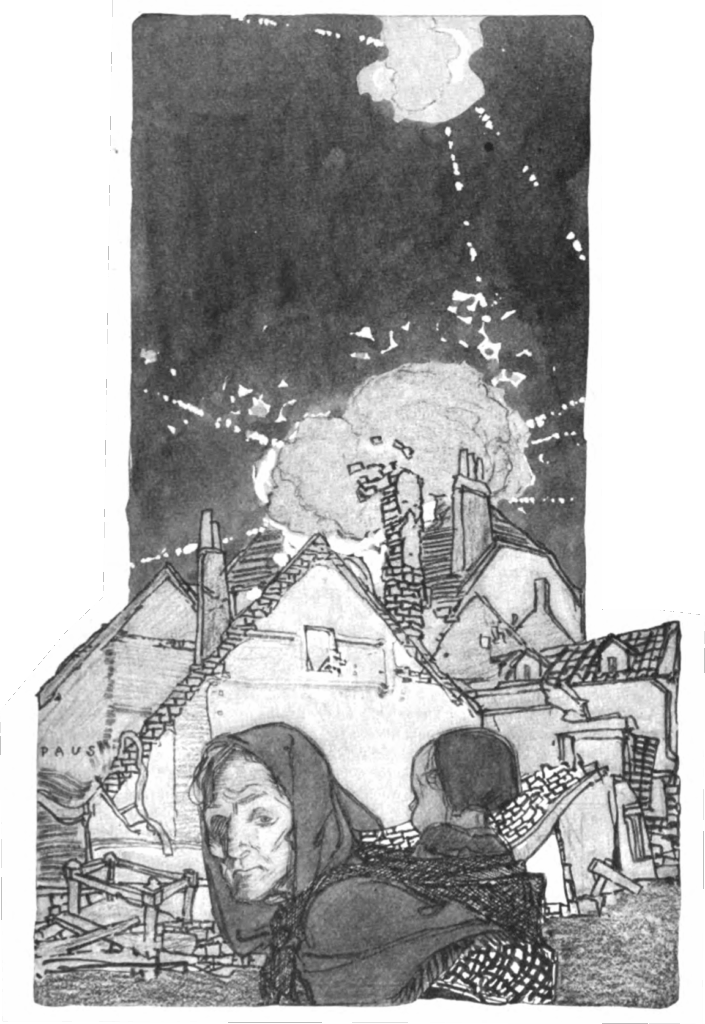

She described cities where life is under military control, like 47 wants in L.A., NYC, and everywhere:

“…Grozny’s reality. The soldiers, rulers of local life, have created a barbaric order in which anyone who knows about the actual conditions of the civilian population can be equated to an enemy spy and has to be dealt with according to wartime laws.”

She raged with exasperation at the treatment of the most vulnerable:

“Why are refugees being shunted from one place to another like so much unclaimed luggage? Why so little respect for people’s feelings and desires? We are continuing to create a nation of outcasts who lack all civil rights. Is it deliberate? I’m afraid so.”

She wrote about the despair of being the only one trying to address grevious wrongs, and how your closest friends and family cannot bear to hear about it, thinking they can escape through ignorance:

“Everyone is tired of this war. Even of talking about it. At least, in my native Moscow. When you tell even very close friends and relatives on your return about that other world you are met with disbelief. A shadow of doubt crosses their faces and they think to themselves: ‘There she goes again, making up these hellish stories. Don’t bother us. You’d do better to start thinking about the New Year celebrations.'”

“…even close friends don’t believe my stories after my trips to Chechnya, and I have stopped explaining anything, and just sit silently when I’m invited anywhere.”

Contrary to popular belief, those who face painful realities are not debilitated by the knowledge. As Noam Chomsky answered in the 1980s, finding out what’s going on isn’t depressing, it’s elevating – because now we can do something about it. When Anna’s editor in Words, Dmitry (Ciaran Hinds), admonishes her, “Don’t let the things you write upset you” she replies, “They don’t. I start off upset, then I write.”

She wrote of how imperial cruelty, ignored by the imperialist’s population, always comes back on the population that ignored it, that pretended such crimes against Others was no concern of theirs, Chechnya to Palestine:

“…there is no getting away from the truth that it was first tried out in Chechnya. It was precisely at the time of Putin’s ascent of the Krremlin throne, to the din of the bombing at the beginning of the Second Chechen War, that Russian society first made a tragic and wholly immoral error because of its traditional unwillingness to think clearly. Our society ignored what was really going on in Chechnya, the fact that the bombing was not of terrorists’ camps but of cities and villages, and that hundreds of innocent people were being killed. It was at that time that a majority of the people living in Chechnya felt, as they still feel, the complete and diabolical hopelessness of their situation. It was when, taking away their children, fathers and brothers to who knows where and for who knows what reason, the military and civilian authorities said baldly (and still say), ‘Stop whingeing. Just accept that this is what the higher interests of the war on terrorism require.’

Russian society kept almost entirely quiet for three years. The vast majority tacitly condoned this behaviour in Chechnya and ignored those who predicted it would come back to haunt them, since a government which has got away with behaving like this in one part of the country would not stop there.”

It is arguable which city in the USA hates 47 the most – we all want that crown. But like New York City’s hatred of Queens-born 47:

“Demonstrations in St. Petersburg are the most energetic and outspoken in the country; Putin is least loved in his native city.”

War of Words’ closing credits features pictures of dozens of journalists worldwide who have been assassinated, including John McNamara, who was killed with 4 other journalists in the 2018 Capital Gazette shooting. It is a startling and powerful reminder of the importance of their work, and why tyrants seek to undermine the media’s credibility.

Words opens with Anna’s unrelenting challenge to us:

“Do you still think that the world is vast? That if there’s a war in one place it has no bearing on another? And that you can sit it out in peace – ignoring all you see?”

So much of her writing is committed to this attitude, this confrtonation, and her lasting question, and demand:

“Well, what are you going to do about it? We’re living in times when the state authorities are entirely without shame.”

“You can see where all this is leading. By tolerating such things on our own doorstep and allowing the State’s officials to perform these acts of violence against us we shall very soon have our own Pinochet. We shall be so relieved, in fact, when he comes that we’ll throw ourselves at his feet, and beg him to save us.”

“…we will only remain united in future if we act together now. Otherwise we shall become so many wild and hunted wolves each retreating to hide in its lair.”

And her tantalizing reminder:

“The authorities’ apparent contempt for their own citizens stems from their fear of us. They cannot face our grief, they cannot admit their own shortcomings or acknowledge their responsibility for the many victims…”

But we can face it. We are the only ones who ever have.