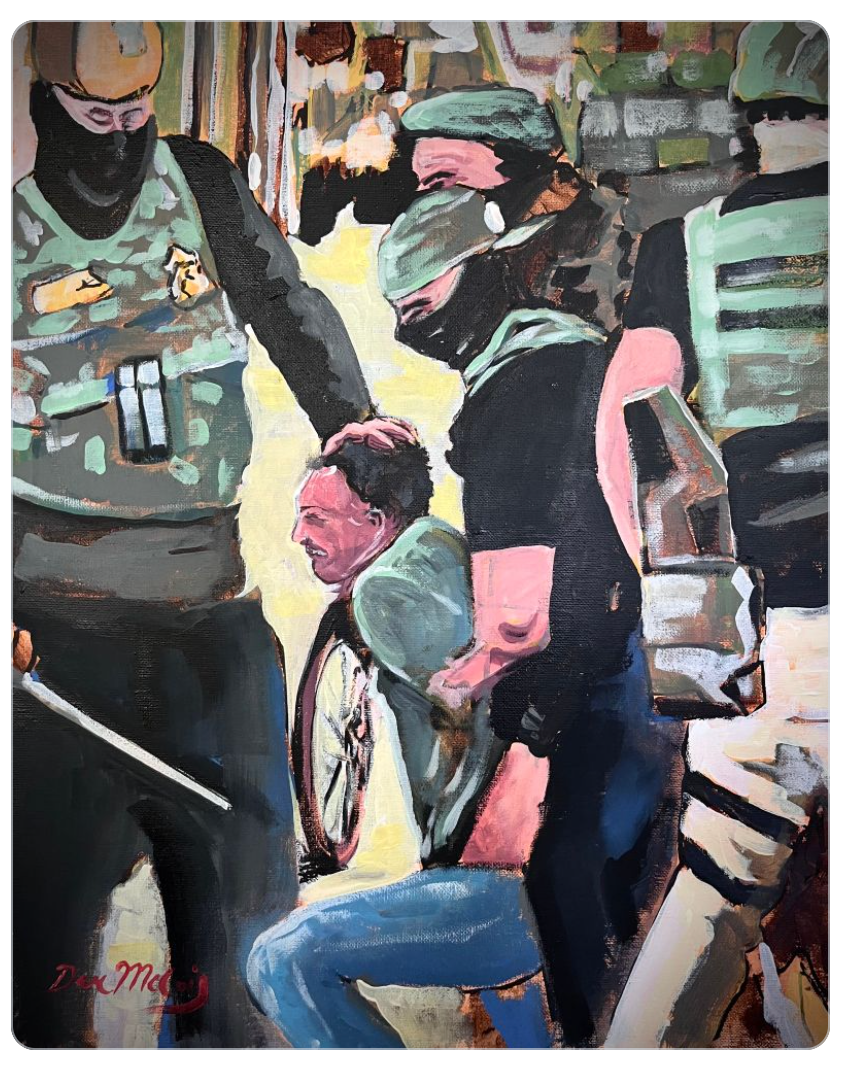

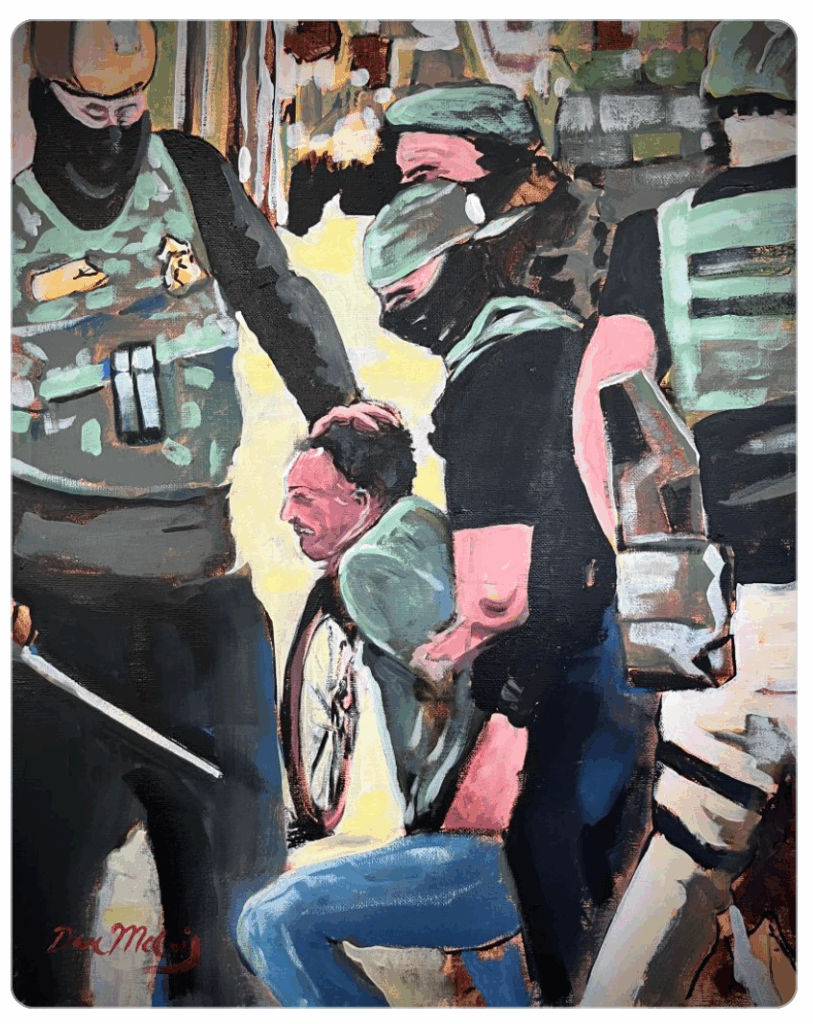

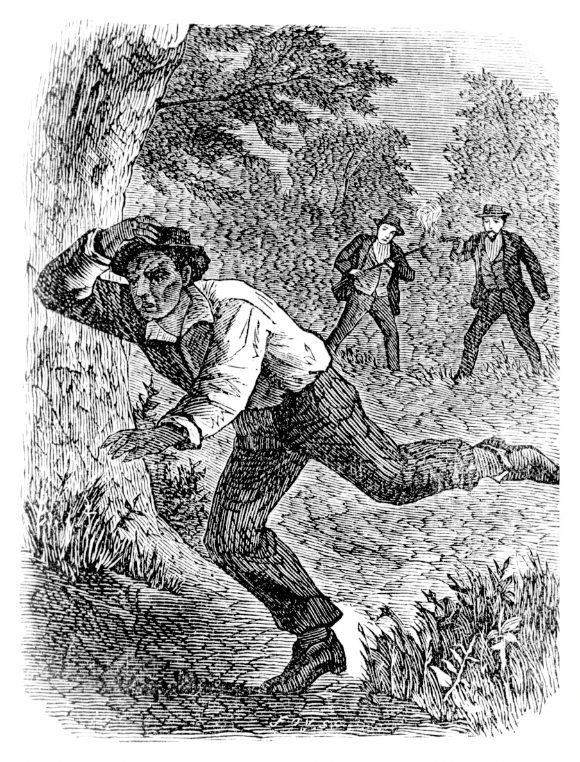

ICE, with faces covered, lurk at courthouses and outside homes and workplaces – and when the person they kidnap is taken away, how are we to know who the kidnappers really are? In macabre tribute to our colonial legacy of kidnapping and slavery, ICE’s Gestapo-type disappearances continue to shock and outrage anyone with an eye to see.

by Dan McCoig Art – bsky

It is only a matter of time before the Trump administration and ICE start referring to “the spirits” – it will be “the spirits” that nabbed Mahmoud Khalil and Rumeysa Ozturk and the thousands of others kidnapped. After that, the rest of anyone they choose will be “spirited away” by “the spirits” acting under the supervision of ICE, as when Trump claimed he could not free Kilmar Abrego Garcia, and was joined in this powerlessness by El Salvadoran president Nayid Bukele. And if the people who imprison a person cannot free that person, it must be The Spirits.

“Spirited away” is a euphemism that has been with us since even before 1776, and it is a bitter phrase. It is synonymous with “trepanned” or “shanghai’d” or “kidnapped” – except that “spirited away” allows the speaker to cleave any human agency from the happening, because they were “taken by the spirits.”

What happened to Paddy McGee? No one knows – he was spirited away.

So no one knows? The kidnappers knew; the prison-keeper knew; the judge who approved the sale of “indentured servants” or “redemptionists” knew.

(Called “redemptionists” because they were “redeeming” the cost of their travel to their employer by working for them; this is similar to the insulting language used to talk about debt “forgiveness”; or the fact that imprisoned people often have to pay a debt to get out of prison. Even 4-year-old Dorothy Goode in 1692 Salem couldn’t get out of jail just because she was no longer accused of witchcraft; someone needed to pay for all the food she ate in the Salem dungeon, the 2 blankets, and the tiny shackles used to confine her – a total of 4 pounds, 6 shillings, and 4 pence. What would that be in crypto?)

British gentleman William Bullock wrote in 1649 about these expense bills for the kidnapped:

“The Servants are taken up by such men as we here call Spirits, and by them put into Cookes houses [cafeterias] about Saint Katherines, where being once entered, are kept as Prisoners until a Master fetches them off; and they lye at charges in these places a month or more, before they are taken away, when the Ship is ready, the Spirits charges and the Cooke for dieting paid, they are shipped…”

“The usual way of getting servants, hath been by a sort of men nick-named Spirits, who take up all the idle, lazie, simple people they can entice, such as have professed idleness, and will rather beg than work; who are persuaded by these Spirits, they shall goe into a place where food shall drop into their mouthes, and being thus deluded, they take courage, and are transported.”

Margaret Patricia writes of these “delusions” in “White Servitude in the American Colonies”, and about the

“…so-called ‘spirits’ or ‘crimps.’ The profits of this business were so great that no class was exempt from its ravages: men, women, and children were enticed on board ship by all kinds of pretences.”

These “spirits”, and the people who referred to them, were just ordinary criminals making money off the misery of the poor and (usually) powerless – that is, as powerless as most of us would be if ICE came for us. Historian A.E. Smith wrote in 1934:

“A much larger portion of our colonial population than is generally supposed found itself on American soil because of the wheedlings, deceptions, misrepresentations and other devices of the ‘spirits.'”

by Dan McCoig Art – bsky

12-year-old James Annesly is the case of a famous somewhat-powerful person who was taken by the “spirits” when his uncle Richard conspired to have James kidnapped from Dublin and indentured into Newcastle, Pennsylvania, in 1728. James spent a dozen years indentured in Delaware before escaping, without spirits, and returning to Ireland.

Another case involving a wealthy person illustrates the class difference, and how the wealthy could save themselves and others if they chose. As told by Historian John Wareing:

“In 1664, Lady Yarborough used her influence to obtain a warrant for the master of a poor boy she had in her care to search ships for him after he had been ‘stollen away by spirits they call them.'”

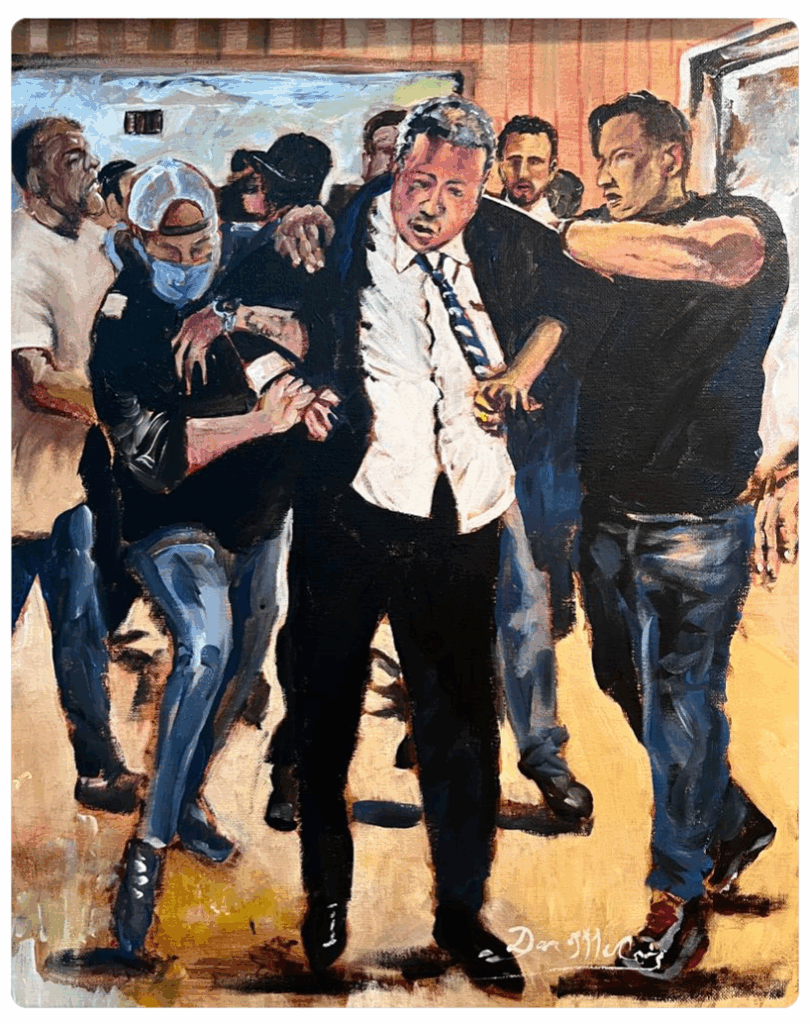

New York City Comptroller Brad Lander, after being arrested by ICE, spoke to this class difference in our own time:

“I am just fine … but I’m going to sleep in my bed tonight, safe with my family.” But the man Lander was helping, Edgardo: “Edgardo is in ICE detention, and he’s not going to sleep in his bed tonight. So far as I know, he has no lawyer. He has been stripped of his due process rights by a government and a judge that owe him a credible fear hearing before they deport him.”

by Dan McCoig Art – bsky

While ICE today has used the possibility of being granted citizenzhip to lure people to being kidnapped, historian Philip Alexander Bruce explains the colonial-era enticements used to lure victims, and the pervasiveness of the practice:

“It was no uncommon thing at this period to find men and women in the seaport towns, but especially in London and Bristol, who earned a livelihood by alluring very young persons to their houses by gifts of sweetmeats, and who cropped the hair of the victims thus secured, so as to alter their appearance beyond recognition, and then disposed of them to persons engaged in sending out laborers to the plantations.”

“In all parts of England at this period, the expression ‘to spirit away’ became one in common use, and it was full of mysterious and terrifying significance to the popular mind; when any one who belonged to an inferior station in life disappeared without leaving any explanation of his absence from the community in which he had been living, he was said to have been ‘spirited away,’ and this whether he had gone out as a servant to the English Plantations or not. The persons who had earned by their peculiar occupation the name of ‘spirits’ were invested with even greater awe than body-snatchers in our own time.”

Who else but those “invested with awe” would dare to kidnap our fellow citizens away from us?

When it comes to being “spirited” or “trepanned,” it was women who first took the abuse:

“the first cargo of emigrants that were exchanged in the colonies for money … was a shipment of young women sent by the company to make wives for the settlers. The alleged kidnapper was one Owen Evans…”

The complaint against Evans, written by a Justice of the Peace of Somerset, used another euphemism to charge that he

“had commanded the constable of the hundred of Whitleighe and others to press [kidnap] him divers maidens to be sent to the Bermudas and Virginia…” The police “constable affirmed that said Owen required him in His M[ajesties’] name to press him five maidens with all speed … and on demanding to see [Owens’] commission reviled and threatened that he should answer it in another place.”

And in our time, ICE arrested Ras Baraka and LaMonica McIver for committing no crime but trying to investigate an ICE facility in their city/state; facilities that are widely known for rampant sexual abuse and other abuses.

Another constable claims that Evans “required him to press some maidens, else would he procure him to be hanged.” After being “committed … to gaol,” the Justice writes that,

“His undue proceedings breed such terror to the poor maidens as forty of them fled out of one parish [Ottery] into such obscure and remote places as their parents and masters can yet have no news what is become of them.”

Like Momodou Taal choosing to leave the USA because ICE was going to get him anyway. We can see this terrorized self-exile in the cancellation of Chicago’s Cinco de May parade for fear of ICE; or in the reported large number of people no longer seeking health care, going to school, or going to work, because ICE might kidnap them there and spirit them away.

Evans, and the men he worked with, were such shits that a later complaint claims that he paid “twelve pence to one Jacob Cryste to press Evans his [Cryste’s] daughter.”

So prevalent and terrible were these constant kidnappings of women, that a famous song of warning was written around 1690:

“The Trepann’d Maiden

or, The Distressed Damsel”

with the subtitle:

“This Girl was cunningly Trappan’d, sent to Virginny from England,

Where she doth Hardship undergo, there is no Cure it must be so:

But if she lives to cross the Main, she vows she’ll ne’r go there again”

The song begins:

“Give ear unto a Maid, that lately was betray’d,

And sent into Virginny, O:

In brief I shall declare, what I have suffer’d there,

When that I was weary, weary, weary, weary, O.”

Stay away from Virginia, and the spirits, the song insists, if you have any power at all to do so.

Philip Alexander Bruce tells of an “Elizabeth Smalridge [who] had been persuaded by a soldier to enter the ship, where he had sold her into bondage.” It was not because Elizabeth was stupid – but desperate, Bruce writing,

“…they played upon the ignorance of the simple-minded, the restlessness of persons in the lower walks of life who were anxious for a change, the despair of those who were sunk in hopeless poverty, and the eagerness of those who had been guilty of infractions of the law to escape from the country.”

John Wareing would reference similar tactics:

“A Memorial from the Lord Mayor and Court of Aldermen of the City of London to the Privy Council raised a more general and widespread concern about public order issues when they asked for action to suppress ‘certaine persons called spirritts (who, without lawful passes) do inveigle and by lewde subtilltyes intice away youth, against the consent either of their parents, friends or masters.'”

Bruce wrote about the desire to import servants into the colonies that was increasing the traffic of the spirits – similar to the growing demand by G4S (formerly Wackenhut) and other prison businesses, to make profits out of people kidnapped by ICE:

“So great was the demand for these youthful laborers that in one year alone, 1627, fourteen or fifteen hundred children who had been gathered up in different parts of England were sent to Virginia. In 1629, the Governor took steps to obtain a large number from the city of London. This demand continued during the remaining portion of the century.”

Like ours, it was an age of kidnapping, and young men – and old – were constantly being kidnapped (“pressed”) into military Naval service. David Grann’s The Wager tells of retired injured sailors being kidnapped into service in 1741, the Crown showing the same compassion for Veterans that Trump demonstrates:

“In desperation, the Navy took the extreme step of rounding up … five hundred invalid soldiers from the Royal Hospital … a pensioner’s home established in the seventeenth century for veterans who were ‘old, lame, or infirm in [the] service of the Crowne.’ Many were in their sixties and seventies, and they were rheumatic, hard of hearing, partially blind, suffering from convulsions, or missing an assortment of limbs. … [The Captain] watched the incoming invalids, many of them so weak they had to be lifted onto the ships on stretchers. Their panicked faces betrayed what everyone secretly knew: they were sailing to their deaths.”

“Spiriting” was such a well-known and constant presence, that accusations of being a Spirit could be countered with accusations of libel. Wareing tells us that,

“In 1656 Susan Jones was bound to appear before the Middlesex Sessions ‘to answer the complainte of Rebekah Allen for raisinge a tumult against her and callinge of her “spirit” and saying she had caused her to be sent away on shipboard to be sent beyond seas.'”

Sent beyond the seas. So much like Kilmar Abrego Garcia, Bronx 19-year-old Merwil Gutierrez, and hundreds or thousands of others who have been sent beyond the seas to El Salvador or Venezuela or Sudan. And that’s no libel.

Another example from Wareing:

“…John Cole to appear in 1659 was ‘to answer for reviling Capt William Staffe in the street for calling him “Spirritt” which is so infamous a name that many have been wounded to death, and the Captaine is much beaten and bruised by the multitude, beinge a verie aged man.'”

But Spiriting was performed and condoned by the powerful, because it was useful to them, and without it they could not have stolen an entire continent. And they considered it their right to steal people in England, as they considered it their right in the rest of the world, too. Wareing cites A.E. Smith’s work on the topic in his book Colonists in Bondage, Smith writing that,

“a merchant who spent from four to ten pounds on getting a servant to America could count on selling him for from six to perhaps thirty pounds. This was a comfortable profit, despite the large risks that sickness or death might scale down the value of the cargo, but it was not exorbitant, for the time involved in these transactions was long and the total value of any shipload not great. The real point [for merchants] was that servants provided a convenient cargo for ships going to the plantations to fetch tobacco, sugar, and the other raw products available.”

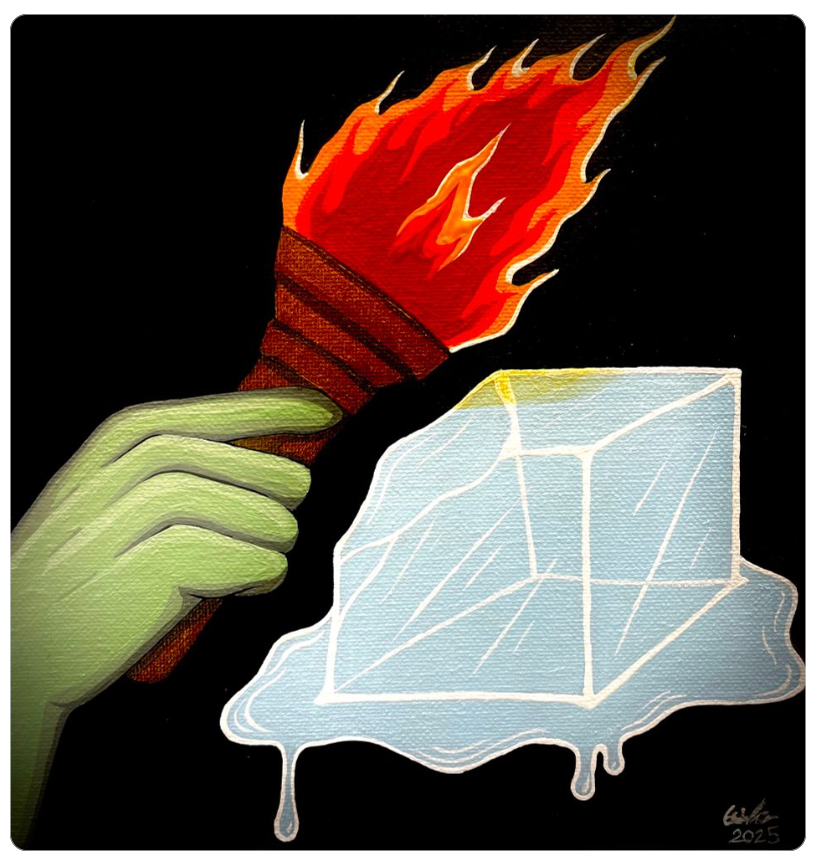

Not only is the term “spirit away” still in use today, but the dictionary definitions are a valuable revelation. The OED has 3 definitions of concern for us:

5.a.

“To entice away or kidnap (a person)” “in order to supply free or indentured labor for the West Indies or North America.” The definition stresses that this is used, “When in the context of supplying labour for the West Indies or North America, never used with reference to the traffic of African slaves.”

There was no need to cover-up “the traffic in African slaves” with a euphemism because the white power structure believed (or claimed to believe) that African people were supposed to be slaves based on their complexion. Only “white” servants needed the opacity of being “spirited away” to assuage the culture’s conscience and allow it to believe things about itself that it knew were not true. (Like lamenting every Christmas Eve about there being “no room in the inn” for refugees Mary and Joseph, while forsaking Mahmoud Khalil, his 8-months pregnant wife Noor Abdalla, and their unborn child – this is done by an anti-abortion movement that cares about women and children almost as much as the soul-sellers did.)

The 5.b. definition hits onto the “spirit” of the phrase:

“Of a supernatural being: to carry off, cause to disappear.”

Of course – it wasn’t the kidnappers, jailers, planters, judges, kings, emperors, popes, ship captains, agents, port of call officers, etc. that were all working in league together to make a profit off the lives of people they’d made sure were poor to begin with. No. Some “spirit” came and took them away, and there’s no accounting for spirits.

A.E. Smith explains this gaggle of authorities who ruled it over the poors:

“…the kidnappers and spirits instead of being deplorable outlaws in the servant trade were the faithful and indispensable adjuncts of its most respected merchants.”

So similar the aforementioned Wackenhut (now G4S) and all the other prison institutions, and the people who own them, who make huge money off of the existence of prisoners – like the new concentration camp in the Florida everglades.

“The very everglades of Florida,” Frederick Douglass wrote, “beyond the remotest hope of emancipation.”

Do any of these places want to go out of business? No. Then they’ll do everything in their power to make sure the human beings who they turn into capital-producing prisoners keep coming, and stay. These institutions have a vested interest in crime taking place, and in the public being very afraid of crime and criminals.

5.c. hits on the euphemism more strongly:

“To convey rapidly and mysteriously or secretly, as though by the action of a supernatural being; to transport with speed.”

Like the speed Trump tries to use to illegally deport people to El Salvador or Venezuela.

“As though by the action of a supernatural being.” But not actually by the action of a supernatural being, but the action of a human being.

Smith explains things in Colonists in Bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America 1607-1776:

“…pressure was supplied by the emigrant agent, generally called during the seventeenth century in England a ‘spirit’ because of his tendency to use improper methods of persuasion, and known in Germany as a ‘Newlander,’ or more venomously ‘Soul-seller.’ Such agents were paid by ship captains, merchants, proprietors, generally at a fixed rate per head for all recruits whom they produced ready for transportation. Their activities were at the root of all emigration during colonial times in those periods where a true ‘fever’ was running its course.”

One well-known domestic example of being spirited away is Solomon Northrup, who told his story in 12 Years A Slave: he was “enticed” by a job prospect and “spirited away” while in New York State by “soul sellers” who sold him into slavery; and since Northrup disappears from the historical record 6 years after escaping slavery, it is terribly possible he was “spirited away” again.

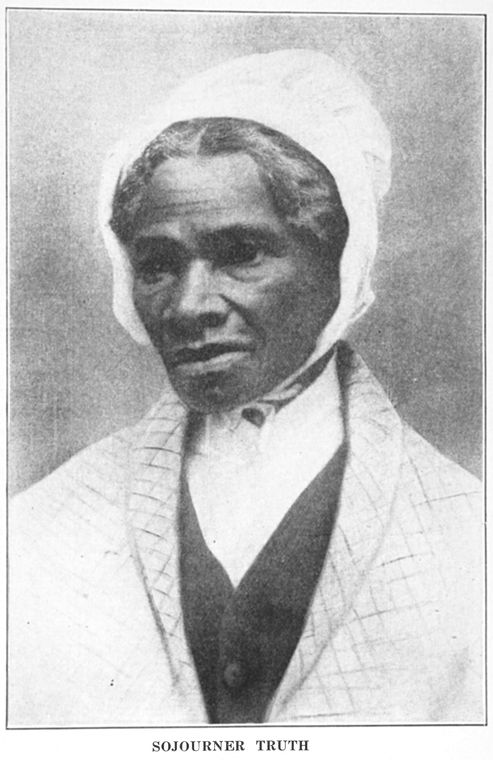

Another example of domestic “spiriting” was the illegal sale of Sojourner Truth’s child out of New York State and to Alabama, against New York law. Sojourner was born into slavery in New York State probably in 1797 – enslaved by Colonel Johannes Ardinburgh, in Ulster County. (Rutgers University recently released information that Sojourner Truth was born into the family of Rutgers’ first president, Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, the brother of Colonel Johannes Ardinburgh.)

So Sojourner was not freed by the 1799 New York State emancipation, but would be freed in 1827 – and her enslaver promised to free her in 1826. But he didn’t.

So she left.

The enslaver – a man named John Dumont – unlawfully sold Sojourner Truth’s five-year-old son, Peter, to a southern enslaver named Fowler, from Alabama.

Alabama was part of what was called “the Deep South” – from where you can never find someone again. That was the belief at the time, and the accounts of enslaved people who never saw their parents or children again after one of them was sold show it to be true.

Fortunately, the man who had sold Peter – a man named Solomon Gedney – was frightened when his lawyer told him he could get fourteen years and a $1,000 fine (about $30,000 dollars in 2025 money). Perhaps a fine appropriate for Avelo airline. Sojourner’s autobiography relates that Gedney,

“secreted himself till due preparations could be made, and soon set sail for Alabama. Steamboats and railroads had not then annihilated distance to the extent they now have, and although he left in the fall of the year, spring came ere he returned, bringing the boy with him…”

Of course Sojourner then had to fight to get her son, and have him not be property. After endless and tireless haranguing of authorities, she won.

But the cost to Peter was immense. Upon his return he was scared of his mother – as the enslavers had indoctrined him against Northerners and anyone but the enslaver – and was physically scarred from tortures that no one can or should endure. No doubt the thousands imprisoned now will retain traumas from their time with ICE.

The phrase “spirited away” is used countless times throughout the centuries. Frederick Douglass uses it to write about his constant fear of being returned to slavery.

“While … there was little probability of successful recapture, if attempted openly, I was constantly in danger of being spirited away, at a moment when my friends could render me no assistance.”

Douglass was warned about such dangers on his escape from slavey in 1838; upon reaching New York City and

“walking amid the hurrying throng, and gazing upon the dazzling wonders of Broadway … wandering about the streets of New York city and lodging, at least one night, among the barrels on one of its wharves … I kept my secret to myself as long as I could, but was compelled at last to seek some one who should befriend me without taking advantage of my destitution to betray me. Such an one I found in a sailor named Stuart, a warm-hearted and generous fellow, who, from his humble home on Center street [in Five Points], saw me standing on the opposite sidewalk, near ‘The Tombs.’ … He took me to his home to spend the night,”

and introduced Douglass to the New York vigilance committee. After Douglass and his fiance were married by the Rev. J. W. C. Pennington (another person who escaped slavery), Douglass went on to Massachusetts, considered safer than the New York streets haunted by spirits kidnapping people escaped from slavery.

In 1839, Harriet Powell successfully escaped from her Southern enslavers while they vacationed in Syracuse, NY, and the papers printed the enslavers’ notice that,

“It is believed that she has been spirited away from the service of [the enslaver] by the officious and persevering efforts of certain malicious and designing persons…”

So not by spirits then – or at least by good spirits, finally.

Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya quotes a Russian soldier using the term in the 1980s, in an attempt by Russia to limit culpability for killing real people:

“Yesterday they slashed a dukh to pieces in the drainage channel over there.”

“Dukh” (lit. “spirit”), Soviet army slang for their opponents in Afghanistan.”

The phrase, which continues to be used to this day, shows up in Joan E. Marshall’s “Parents and Foster Parents, Shapers of Progressive Era Child Saving Practices” which has the phrase in the mouths of those who took poor children away from their families, in Indiana:

“Interest came to be centered on the care of dependent children as a panacea for this visible poverty. Many progressives thought that moving these children from the bad influences of their home environment to a more wholesome one would free the United States from poverty, crime, and vice in the future.”

“Despite the association’s vigilance, determined parents managed to ‘steal’ their children. … The TCCHA attempted to make it plain that placed out children now ‘belonged to the home’ and held many discussions about ways to get back children who had been ‘spirited away’ by their parents.”

Anne Frank does not use the phrase, but describes the type of kidnapping horror unfolding all around her in January 1943, that will chill the spines of many in the U.S.A. today:

“It is terrible outside, day and night more of those poor miserable people are being dragged off, with nothing but a rucksack and a little money. On the way they are deprived even of these possessions. Families are torn apart, men, women and children all being split up. Children coming home from school find that their parents have disappeared. Women return from shopping to find their homes shut up and their families gone. … Everyone is afraid.”

Eventually, there was some colonial-era official movement against these “spirits” – but only because it was inconveniencing the wealthy. Bruce writes,

“In 1664, the English merchants presented a petition condemning the action of these persons, not on the ground that it resulted in so much injustice and inhumanity, but because it offered to so many worthless individuals who had been spirited away with their own consent, an opportunity to say, after having received a large quantity of clothing and been furnished with food for a great length of time, that they had gone on board ship in opposition to their own wishes and had been detained there by force.”

The nerve.

Bruce also relates cases where,

“Warrants for the return of children and the discharge of grown persons who had been inveigled on board vessels were issued in great numbers and served upon the captains in command. … A second warrant was sworn out at the same time for the seizure of the person who had been guilty of the abduction complained of, this person being generally some notorious spirit who was suspected of habitually committing the crime.”

These are the types of warrants that could be issued against ICE officers who unlawfully kidnap people off our streets.

Not that this 1664 petition was successful – nor was the 1671 “act” which failed in Parliament, and as Wareing writes,

“referred to spirits as ‘sundry wicked persons’ and proposed the remedy ‘That what person or persons soever shall by any deceit, or force Steale any person or persons, to the intent to sell or transport them into parts beyond Sea. And the accessories to such offense, shall suffer death as Felons without clergy.'”

At this time in the late 17th century, as Bacon’s Rebellion and its aftermath shocked the powerful, the powerful began setting up a color-based slavery system, desperately wishing to keep laborers separated by social class distinctions, Wareing writing that,

“This concern that English people were being taken into slavery was made clear in 1676 when the Lords of Trade and Plantations in their discussion of the laws of Jamaica expressed themselves ‘not pleased with the word (Servitude) being a mark of bondage and slavery, and think fit rather to use the word (Service) since these servants are only apprentices for years'”

– and not enslaved for life.

But for some time to come, Spiriting Away would remain a profitable and legal means of emptying European cities of people the rulers of those cities did not value as citizens, and populating the New World with European laborers to displace First Nations people, and perform the work that made our rulers so rich and powerful. People they thought had no value – but could have cured cancer. Just like ICE trying to deport the Harvard scientist who is doing sophisticated cancer research that might even save the life of an ICE, or an ICE’s child.

Wareing ends his essay solemnly:

“stealing horses continued to be punished more severely than stealing children.”

Europeans Spiriting Away their poor in this manner was largely ended by the color-based importation of enslaved Africans who continued to be kidnapped from their homes for many decades to come, making even worse the heinous tragedy of soul-stealing to the Americas.

The purpose of calling all these kidnappings “spirits” is to deny their reality, and to avoid being forced by public revulsion to put a stop to the practice. “It was not I who kidnapped your poor child, Madam, it must have been a spirit. Cheery-bye.” In our time, ICE kidnaps with masks, and judges make cash for sending kids to juvenile detention. And prisons like El Salvador’s CECOT are a continuation of the money-making kidnapping exploitation that was supposed to have been ended here by the Civil War. And yet it does happen. Both through the vulgarity of exclusion and hate, and the ruthlessness of a system that turns kidnapped people into cash for every agent along the journey from a poor London street to a tobacco field in Virginia. From a union job and a family home in Maryland, to a prisoner in a foreign land with no rights. And it didn’t come in a flash. We were warned. As Todd Snider sang back in the bad old GWB days of war and torture of 2007,

“We who have nothing, and most likely will

’til we all end up locked up in jails

By conservative Christian right wing Republican straight white American males.”

The spirits still rule the darkness, spirting away all they can: those who call for the mass deportations, those who support them, those who carry them out, those who focus on anything but what’s happening.

But for all the darkness in The Spirits, there are always other spirits intent on freedom, like that gained by Mohsen Mahdawi and Rumeysa Ozturk and Mahmoud Khalil. Spirits like you and me and all those dedicated patriotic freedom-lovers we’ll never know, but that history will name as the defiant Spirit of the Age – may it never be spirited away.

by Georgia Bean – bsky – ig